140 A.D; LONGINUS, ROMES VAMPIRE EMPEROR.

During the early days of the Roman Empire, vampires were hunted and destroyed by an elite squad of the Legion. The Roman ability to control vampires was widely respected and made it easier for them to colonize far flung nations. Captured vampires were brought to the the Coliseum in Rome, where they fought lions, tigers and Christians in nighttime battles.

A frequent spectator at these contests was the young Emperor Longinus, who began his reign in AD 68 at the age of 17. Longinus' favorite was Brittanicus, who was captured in England in AD 65 and had developed a formidable record as a vampire-gladiator. Against the advice of his Praetorian bodyguards, Longinus had Brittanicus installed in a lavish suite inside the palace. One night, Longinus paid his guest a visit and the inevitable happened: Longinus was bitten and became Rome's first vampire emperor.

The vampire emperor's short reign over Rome was disastrous. The Praetorian Guards who had defended Longinus were expelled from the Palace, and vampires became protected throughout the Empire. Longinus and Brittanicus led other vampires on nightly hunting parties through the streets of Rome. Vampirism, which had previously been contained within Rome, exploded.

Facing a dire future, the expelled Praetorian Guards took it upon themselves to save the Empire. On a warm summer morning in AD 69, about a dozen Praetorians burst into the palace. The vampires, drowsy and bloated from the previous night's feast, were easy pickings and the Praetorians methodically dispatched them, saving Longinus for last. He was decapitated, and his head was stuck on a pole outside the city gates as a warning to any vampires who might want to venture into Rome.

773 A.D. CHARLEMAGNE DEFEATS QUADILLA THE VAMPIRE.

The decline of the Roman Empire left Europe in a turbulent state. In an absence of any central authority, the countryside was overrun by a series of vampire armies, each more terrifying than the last. The armies, generally consisting of between 50 and 100 vampires, would swoop into towns on horseback in the dead of night, howling with bloodlust. The only saving grace for the people of Europe was the limited range of these armies, as it was difficult for them to stray far from their daylight havens. But in the Ninth Century, a charismatic leader named Quadilla united a number of vampire armies into a mobile, fearsome fighting force that had many in Europe believing the end of the world was nigh.

Quadilla grew up riding horses and tending goats and sheep on a farm near the Po River in northern Italy. His bucolic upbringing came to an abrupt end at age 16, when a corrupt local priest confiscated his family's property. The evicted family had the distinct misfortune of settling in a gypsy camp shortly before it was set upon by a small vampire army. Quadilla's parents were killed; he was bitten, then taken away to join the army.

Quadilla quickly distinguished himself as a great horseman and fearless warrior whose ambitions outpaced the limited scope of his precursors. Quadilla envisioned himself as the leader of a vampire empire stretching from Gibraltar to the Danube. With his great skills as an orator, Quadilla was able to convince local vampire armies to join his cause. After winning important victories against the Lombards, the army began a slow, inexorable march down the Italian peninsula toward Quadilla's ultimate goal: the papal leadership in Rome.

Quadilla's offensive was greatly aided by the Italian topography. Each night, he would raid a village for blood, then take shelter in the numerous caves of the Apennine Mountains. Remindful of the corrupt priest who took his boyhood home, Quadilla saved special cruelty for houses of worship. He plundered monasteries and left the heads of priests impaled on stakes outside the churches. These horrific displays convinced many that Quadilla was the Devil himself, and that the advances of his army represented the end of the world prophesied in the bible.

In December of 772, Quadilla's army took Siena, leaving it only 150 miles from Rome. As the Italian capital swelled with refugees, the stories of Quadilla took on an outsized, mythological scale. Eyewitnesses told of a ten-foot-tall, fire-breathing man with horns, cloven hoofs and a tail. While none of these stories were true, they surely unnerved Pope Hadrian II. The Pope, facing desertions in his own army, sent envoys to the Frankish Kingdom of the north to ask the young king Charlemagne for help.

Though Charlemagne had come to power only two years earlier, at age 29, the six-foot-six-inch King of the Franks already had ambitions to match his towering frame. He wanted nothing less than to rule Europe, and he knew that having the imprimatur of the Pope would help him greatly in his quest. He told the papal envoys that he would take his men into Italy as soon as the snows melted.

In the spring of 773, Charlemagne led his army across the Alps into Italy. He followed the coast south and made camp along the Tiber River north of Rome, not far from the site of Quadilla's most recent assault. Charlemagne had planned to use the camp as a base from which to conduct sorties into the mountains, but Quadilla had different ideas. That night, the vampire army attacked the camp and inflicted heavy losses on Charlemagne's army before retreating back to their caves.

As the day dawned, Charlemagne surveyed the wreckage of his camp and realized he could not fight the vampires by conventional means. After breaking his army up into smaller groups and setting them in defensive positions in the hills, he sent his most experienced vampire hunters into the mountains to conduct reconnaissance. That night, the men located the vampire cave network, and as soon as the sun came up, Charlemagne led his army there. Rather than send his men stumbling blindly into the dark caves, Charlemagne had them heap timber onto modified horse carts, light the pile on fire and roll the carts into the caves. The plan worked beautifully: vampires were smoked out into the light and beheaded by the hundreds.

Working from cave to cave, it took four days for Charlemagne's army to kill the last of the vampires. Quadilla himself fought gallantly; though effectively rendered blind by the bright sun, he killed over 20 soldiers before Charlemagne dispatched him with a blow from his sword.

On Christmas Day, 773, a grateful Pope crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor in the city he had saved. During Charlemagne's 47-year reign, Europe enjoyed a relative respite from vampire armies. The fire carts Charlemagne had improvised lasted even longer; they were employed against vampires well into the Eighteenth Century.

In 1974, a team of Italian archaeologists discovered a huge cache of artifacts in caves near the Tiber. Among the finds were armor and weapons bearing the broken cross symbol peculiar to Quadilla's army. A museum was built nearby to house the relics and honor the men who saved the seat of Christianity from a grisly fate.

1530 A.D. LUDOVICO FATINELLI

During the Middle Ages, the scientific study of vampirism was tangled up in religious notions of good versus evil. Vampires were the Devil's foot soldiers, and victims of vampirism were thought to have had some sort of moral failing which left them vulnerable to attack. The large number of prostitute-victims was held up as proof of this. The church, at perhaps the zenith of its power, had a vested interest in keeping this notion afloat, as nervous worshipers tended to spend more time in church and give more money. But the dawn of the Renaissance gave rise to a number of visionary scientists who, at their own peril, began to question previous assumptions about vampirism. And one of them, an Italian named Ludovico Fatinelli, paid for it with his life.

Fatinelli was a native of Florence whose father was employed in the relatively new profession of making eyeglasses. The young Fatinelli took an interest in his father's trade and made his own magnifying glasses to study the world around him. As his lenses got more sophisticated, he was able to discern a world previously unknown to science. His notes from a look at a sample of water from the Arno River capture the excitement of discovery: "I then saw, with great wonder, that in the water were very many little animalcules, very prettily a-moving. The animalcules were in great number, and oft times spun around like a tail." Fatinelli had taken the first recorded look at bacteria.

The young Florentine went on to study medicine at the University of Padua, where one of his teachers was the great scientist and philosopher Galileo Gallilei. While there, Fatinelli, through the use of increasingly more sophisticated microscopes, discovered that "animalcules" also appeared to live in human tissue. From these observations, the young scientist developed the radical theory that it was these microscopic entities, not moral failures, that were the real source of vampirism. Experiments on animals seemed to bolster his hypothesis, and he set to work on a treatise that would summarize his findings and, he hoped, establish his reputation as a great scientist.

In Januay, 1616, Fatinelli published his findings under the title, Treatise on Vampires. Alas, his timing couldn't have been worse. Pope Paul V, worried about the rise of Protestantism, had been taking a hard line against any new interpretation of church dogma and decided to make Fatinelli an example. The young man was brought up for the Inquisition, and when he refused to recant the conclusions in his treatise, he was charged with heresy and brought to trial. Though a simple recantation probably could have gotten him off the hook, Fatinelli stood behind his findings. Judgment was swift: the verdict was guilty, the sentence, death.

On April 23, 1616, a huge crowd gathered in Florence's Piazza Signoria to witness the execution. Fatinelli was tied to a pole atop a pile of logs, which were then set ablaze. The fire ate through the rope securing Fatinelli to the pole, and his left arm flew up in the air. A shriek went through the crowd; many fainted, thinking that the Devil was passing a curse from Fatinelli's body onto them. But the man on the pyre was only flesh and blood. Once the spectacle was over, one of the most important scientists of the time was ignominiously heaved into a pauper's grave, where the church hoped he would be forgotten forever.

It was not to be. Though Fatinelli was gone, his research lived on. For years after his death, illicit copies of his banned treatise made their way through Europe's scientific communities and helped pave the way for important work by scientists like the Englishman Edward Jenner, who created the first vaccine in 1795. Fatinelli had indeed been far ahead of his time: too far ahead, for the church's comfort.

1607 A.D. SHIP OF THE DEAD BRINGS

VAMIPRES TO THE NEW WORLD

The voyage of the British merchant ship Cormorant from Portsmouth, England, to the Caribbean island of Nevis had special meaning for Andrew Oglethorpe. After ten years as a sailor, Oglethorpe had decided to call it quits and live out his days as a fisherman in the British West Indies. And so, on June 15, 1607, the night before his last voyage, Oglethorpe set up shop in a Portsmouth pub and drank to his good fortune.

It wasn't to last. As Oglethorpe staggered toward the docks an hour or so before dawn, a prostitute called to him from the shadows. Inebriated, and facing three months at sea with no female companionship, Oglethorpe eagerly followed her into a dark alley, ignoring the old seafarer's maxim: harlot for hire, might be vampire. No sooner had they found a private spot than the prostitute sunk her fangs into him, and Andrew Oglethorpe's dream of a life of tropical ease was over before it started.

Like many victims of vampirism, Oglethorpe chose to deny what had happened. He boarded the Cormorant and assumed his duties as the ship left port under the direction of Captain Horatio Wheeler. By nightfall, Oglethorpe was in sick bay with a fever and chills. As Oglethorpe's wounds were not easily visible, the ship surgeon probably confused his symptoms with one of the more common ailments of the day. Eventually, Oglethorpe slipped into a vampiric coma; he was being prepared for burial at sea when he came back to life.

The fate of the crew would have been left to the imagination had Captain Wheeler not been an assiduous journal-keeper. Entries in his log became increasingly ominous as the journey progressed.

August 24th: "For the past three days, we have been sailing through a storm, which has prevented us from continuing a sweep of the ship designed to root out any remaining vampires. Thus far, we have captured and thrown overboard three crew members who were showing signs of the dread disease."

September 14th: "The vampires have barricaded themselves in the hold and, despite my entreaties, none of my crew dares go down there to dispatch them. Our nerves are frayed, as none of us have slept for two weeks. Last night, a man leaped off the boat rather than face another night of this torment."

September 16th: "They are at my door now. There is no hope. I can only pray that God dash this accursed ship against the rocks, lest it deliver its hellish cargo upon some innocent shores."

The captain's wishes would not be met. On the night of September 20th, Cormorant cruised into the harbor of the small Caribbean island of Nevis with Captain Wheeler, now a vampire, at the helm. Native islanders paddled out on canoes to greet the ship, unaware of the awful surprise waiting on board.

From this one ship, the vampire virus would spread rapidly across the Caribbean and the New World. The disaster prompted an overhaul of shipping procedures. Henceforth, all sailors were given thorough physical examinations before boarding.

1842 Vampire investigation bureau established

England's Vampire Investigative Bureau, the world's first and longest serving undead abatement force, was the model for the FVZA and many other organizations across the globe.

The seeds for the VIB were planted in London during the 18th Century, when the city's steep rise in vampirism forced civic leaders to offer substantial rewards for slaying vampires. Mercenary vampire hunters patrolled the streets from sunset to sunrise, collecting five to ten pounds for each vampire they destroyed. Unfortunately, the system was rife with corruption, as many slayers developed too close a relationship with the vampire underworld of London and took bribes for looking the other way or for putting the squeeze on a rival vampire pack.

In 1842, Prime Minister Robert Peel formally established the Vampire Investigation Bureau. Requirements for investigators were minimal at first:

* To be over 21 and under 27 years of age.

* To stand clear 5ft 9ins without shoes or stockings.

* To be able to read well, write legibly and have a fair knowledge of spelling.

* To be generally intelligent and free from any bodily complaint.

Investigators walked beats during the night, armed only with a cutlass. As newer divisions were established in the outer suburbs, the beats became longer and the danger increased, since much of the territory was open fields between residential areas, leaving lone investigators easy prey for roving vampire packs.

Like the FVZA, the VIB in its early incarnation was hardly a model force. Drunkenness and desertion were high. The VIB also was limited by a rivalry with the Metropolitan Police. In the late 1880s, several women were brutally murdered in the Whitechapel area of city. Even though the attacks bore evidence of the work of vampires, the Metropolitan Police refused to hand the case over to the VIB, insisting that the perpetrator was a man. Finally, after a dozen known murders (and probably many more that were undiscovered), the VIB took over the case. VIB officers conducted several raids in the Whitechapel area and destroyed a number of vampires, including Wentworth Smith, a suspicious lodger given to "nocturnal wanderings." While most people believe to this day that the Whitechapel killings were the work of Jack the Ripper, evidence is overwhelming that the murders were in fact the work of a vampire.

Consider the following:

* The murders all took place in the evening.

* Most of the victims were known prostitutes, a favorite vampire target.

* There was a surprising lack of blood around the bodies of several victims.

* Police found body parts in the areas of the murders, including a torso under a railway arch and another torso in the cellar of a new police building under construction. Vampires often will tear victims apart after feeding.

* The murderer sent police half of a human kidney in the mail, along with a note stating that he had eaten the other half. The body of another victim was missing a heart. Vampires have a fondness for gnawing on human internal organs, especially the kidneys, spleen and heart.

* Several eyewitnesses described the killer as "shabby genteel," suggesting a vampire who's been wearing the same clothes for some time.

Lastly, and perhaps most tellingly, the murders stopped after the VIB operation. My personal belief is that the vampire Wentworth Smith was the real Jack the Ripper.

English imperial might stretched the VIB to the breaking point and beyond at the turn of the century. The VIB snuffed out vampire packs everywhere from the mines of South Wales to the slums of Calcutta. The Bureau suffered high rates of suicide and attrition as the vampire population hit its peak worldwide. However, the VIB was able to turn the tide in the 20th Century, thanks to a number of innovations:

* 1908: officers begin working with dogs.

* 1921: zombie division formed, based across the river in Southwark.

* 1934: the VIB Academy founded.

* 1940: first women officers.

As England's overseas possessions shrank, the VIB turned its focus to controlling the undead on the homefront. The U.K.'s small size and relatively isolated geography made the job easier, and the VIB swiftly had vampires and zombies under control. By the early 1960s, the VIB was gone but not forgotten, as they received a roll of honour at Westminster Abbey.

1850 A.D. HAUSSMAN DESTROYS

PARIS VAMPIRE QUATER

The first half of the Nineteenth Century saw a population explosion in European cities. The rural poor and dispossessed flooded urban centers looking for work, and in the process created overcrowded slums rife with disease, crime...and vampirism. All across Europe, vampires found good hunting and ample hiding places in medieval-era neighborhoods, with their tumbledown dwellings, narrow streets and alleyways. Every major European city had a concentration of vampires: the East End of London, Lisbon's Alfama, Warsaw's Old Town. In Paris, so many vampires haunted the neighborhood north of the Louvre that it became known as the Vampire Quarter.

European leaders tried a variety of measures to try and control vampire numbers, including hiring more vampire-fighters and instituting strict curfews. But the number of attacks continued to climb. In 1850, Baron Georges Haussman, Paris' top city planner, offered a radical suggestion: instead of trying to kill the vampires, why not eliminate their habitat? Haussman envisioned a radical reconstruction of Paris, with broad boulevards, spacious squares and a modern sewer system (it was still common belief that poor sanitation contributed to vampirism).

Haussman's plan won approval from French Emperor (and Napoleon grandson) Louis Napoleon and, in 1853, work crews began tearing down the Vampire Quarter, building by building. As crowds of onlookers watched, vampires scurried from collapsing buildings, shrieking and shielding their eyes from the sun, only to be methodically destroyed by special legions of the French Army. In one church, more than 50 vampires were flushed from the crypt. While some French, like writer Emile Zola, protested the widespread destruction of architectural treasures and the lack of interim housing for the homeless, the project did seem to be succeeding in slowing the rate of vampire attacks.

Within 20 years, Haussman had transformed the the old rabbit warrens of the Vampire Quarter into posh neighborhoods with grand boulevards radiating from large squares like the Place de l'Opera. Haussman was celebrated as a genius and European cities raced to follow his lead. From Lisbon to Prague, broad boulevards and wide squares become de rigeur.

However, the canonization of Haussman proved to be premature. After dropping for a short time, vampire attacks in Paris rose to their highest levels ever. To make matters worse, the attacks were no longer confined to Paris' slums. Vampires attacked the well-heeled of the Tuileries, they preyed on students across the river in the Latin Quarter. The great irony of Haussman's work was that, while he had driven vampires from their old haunts, in building Paris' extensive sewer system he had provided them with the perfect place to hide.

For the next 50 years, these vampires, known in Paris as "Haussman's Children," made their home in the sewers, emerging at night for hunting. For a short time, the French stationed troops there, but had to pull out due to high rates of desertion. During World War II, French resistance fighters hiding from the Nazis in the sewers encountered vampires in 19th-Century dress. The development of the vampire vaccine, along with more sophisticated vampire-fighting technology, eradicated vampires in Europe by the mid-1960s. However, in 1971, a rash of vampire attacks along the river Seine paralyzed Paris. French authorities, working with the assistance of the FVZA, tracked a lone vampire into the sewers. The vampire was cornered near the Place des Vosges, and perhaps the last of "Haussman's children" was destroyed.

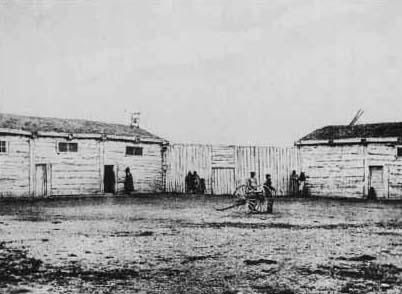

1867 A.D. FORT BLOOD

At about the same time that the FVZA was being organized here in the United States, our neighbors to the north were coming to grips with their own vampire problems. For about 200 years, the huge swath of land in the western half of Canada was controlled by the fur-trading Hudson's Bay Company. The powerful Company was able to keep any vampire outbreaks in check with their own security force. But when the Canadian Confederation Act of 1867 brought the western lands under Canada's control, the Hudson's Bay Company pulled out, leaving the region in a state of disorder. A motley crew of outlaws began moving into the region, and in those days, whenever outlaws congregated, vampirism was sure to follow.

The opportunistic outlaws were mostly Americans who saw money to be made setting up illegal whiskey-trading camps in the region. These scofflaws would trade whiskey with Indians in return for buffalo furs and horses, and the success of their operations sometimes enabled their crude encampments to grow into rowdy towns rife with gunfights and prostitution. Vampirism inevitably took hold, driving out the transients and leaving the Indians to deal with the problem.

There was one whiskey-trading camp that eclipsed all others in debauchery and lawlessness. The camp, which would come to be known as Fort Blood, was the provenance of the Gallatin Gang, a group of low-lifes who had escaped from a Montana prison before making their way to the Great White North and establishing a successful whiskey business. Even by the standards of whiskey camps, Fort Blood was a den of iniquity. With all the prostitutes and transients, it was inevitable that a vampire plague arrived, and when it did, the Gallatin Gang hit upon a novel solution to the problem. Rather than leave town, the Gang struck up an agreement with the vampires in which they would lure Indians to the camp with the promise of whiskey, and then set the vampires on them. In return for providing blood for the vampires, the Fort Blood outlaws were able to keep and sell whatever buffalo hides and horses they took from the Indians. By the early 1870s, Fort Blood had grown into a formidable problem, paralyzing regional trade and settlement and poisoning sensitive relations between the local Indian tribes and the new Canadian government. Now that Canada was responsible for this land, it was clear that Fort Blood had to go.

In 1873, a freshly-minted force of 250 Canadian Mounted Police, or Mounties, traveled west with orders to destroy Fort Blood. But the Gallatin Gang received word of the impending attack and was ready when the Mounties arrived. The Gang repulsed the attack and then, as night fell, unleashed the vampires. All 250 Mounties were killed. The defeat was a stinging rebuke to the newly formed government, and proof that Canada needed a specialized force to fight vampirism in the west.

In 1874, a bill was passed creating the the North-West Mounted Police, Special Division, or the "Specials," for short. 400 men were recruited and trained in vampire combat, and in July of 1874, they left their compound at Fort Manitoba for the long trek west. With 300 horses, 73 wagons and 142 heads of cattle in tow, the Specials followed the Boundary Trail west and made camp at a bend in the Milk River not far from Fort Blood.

Rather than conduct a frontal assault on the fort, the Specials took a more stealthy approach. A small battalion slipped into the fort posing as Indians and, once inside, killed the Gallatin Gang. They then let the rest of the Specials in to finish off the sleeping vampires. By the next morning, Fort Blood was nothing more than a smoldering pile of ash.

For the next several years, the Specials marched from outpost to outpost, slaying vampires and restoring order to the region. Trade and settlement gradually returned to normal, and relations with the Indians improved. However, the frontier nature of the west ensured that the Specials remained busy, especially during the periods from 1882 to 1885, when the railroad was under construction, and 1896 to 1899, during the Klondike Gold Rush. Like the FVZA, the Specials were often pulled away to fight wars on foreign soil, but they still managed to keep a lid on any vampire or zombie outbreaks in their homeland. In 1973, the Specials celebrated their centennial with a ceremony during which they received medals from Queen Elizabeth II. Shortly thereafter, they were disbanded.

1891 A.D. STEKEE’S VAMPIRE RIGHTS

MOVEMENT IN FRANCE

In the summer of 1891, young painter Lucien Steketee arrived in Paris from a small village in Brittany to find a city energized by bold artists breaking free of the confines of Impressionism. Even in a place crowded with painters, the young Breton quickly stood out. Tall and handsome, student of Monet's, friend to Pissaro and Cezanne, he cut a dashing figure in the City of Light.

Like fellow painter Toulouse-Lautrec, Steketee's preferred subject was the nightlife around his atelier in Montmartre. He painted prostitutes, dancing girls, beggars...and vampires. While other artists had painted vampires from memory, Steketee was the first to have them sit for portraits. Despite the danger, Steketee painted over a dozen vampire portraits, and with each one his sense of ease grew. In July of 1892, a vampire suggested to him that Paris' underground catacombs, with their stacks of skulls and bones, would be a more atmospheric backdrop for the portrait; Steketee foolishly followed him there and was set upon by a hunting pack.

Two days later, a local vampire patrol discovered Steketee about to sink his teeth into a young woman. He fled to the nearby Moulin Rouge nightclub and barricaded himself on the third floor. A mob formed outside and began chanting for the vampire's head. In desperation, Steketee stepped out onto the balcony and made an impassioned plea for his life. So persuasive was he that the mob spared him and allowed the gendarmes to take him away to jail.

Steketee had found his calling. Writing feverishly in his dim prison cell, he advanced the radical notion that vampires should be treated like the sick people they were, and hospitalized rather than destroyed. Steketee's broadsides were distributed by his artist friends and created a sensation in Paris. Key to his growing support was his claim that he could live without blood. "Controlling bloodlust," he wrote, "is a matter of discipline and faith." He held himself up as proof, and the public bought it.

With public sentiment on his side, Steketee was released into the care of Madame Mauriello, a wealthy widower and devoted follower. She set him up in her Tuileries mansion, where he continued his crusade, speaking to huge crowds and winning support from politicians and religious leaders.

But away from the spotlight, Steketee was hunting, with the help of Madame Mauriello. Each night, she would prowl the streets of Paris looking for young women to lure back to her mansion under the auspices of posing for a famous artist. Once there, the women would be plied with wine until Steketee emerged, fangs flashing. He kept the "newly converted" in his service as a sort of harem.

The arrangement was shortlived. Early on the morning of December 12th, 1892, a terrified girl arrived in the police station claiming that she had narrowly escaped the clutches of a vampire. Police officers followed her back to the Mauriello mansion and discovered the pack. Word spread, and for the second time in his life, Lucien Steketee found himself hiding out from an angry mob. But this time, there was no escape: the mob burned the mansion to the ground, with Steketee, Mme. Mauriello and the young vampires inside.

Steketee's body was never found, leading to speculation that he had escaped; a suspicion strengthened during World War II, when several members of the French Resistance reported seeing a man resembling Steketee prowling the sewers. To this day, he is said to emerge from underground on the anniversary of his death to claim a victim. Which is why, before nightfall on December 12th, suspicious Parisians hang garlic and crosses over their doorways.

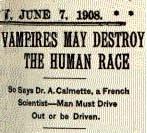

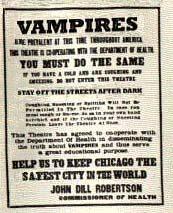

1905 VAMPIRE POPULATION

WORLD WIDE NUMBERS

HIT ONE MILLION

At the turn of the Nineteenth Century, a growing, increasingly urban population, along with rising immigration, contributed to a spike in vampire numbers. In a widely-published 1905 vampire study, FVZA scientists estimated the worldwide vampire population at one million.

The vampire population boom forced world leaders to take drastic measures to try and slow the spread of the plague. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt ordered a curfew in every city and town in the country. At dusk across the land, curfew sirens rang out as children ran in from their play and cities fell dark. The curfew was economically devastating for restaurants, theaters, bars and nightclubs, and led to a mini-Depression. President Roosevelt also authorized an emergency vampire relief fund, with most of the money going to the FVZA to hire more people and upgrade their equipment. In addition, every branch of the Armed Forces was called into service to help the Agency.

Large cities were hardest hit by the vampire explosion. Early each morning in London, boatmen would make their way west along the fog-shrouded Thames, stopping at various wharfs to pick up vampires that had been destroyed the night before. The sight of a withered old boatman slipping silently through the fog, his boat heaped with vampire corpses, was one of the indelible impressions of the day. Eventually, the vampire corpses would be brought to the Battersea power station for incineration. At its peak, Battersea station was burning over one-hundred vampires a day.

Other cities took more dramatic steps to combat the rise in vampirism. In Bombay, India, the city's old quarter, with its narrow streets and numerous homeless people, had become a a breeding ground for vampires. When extermination efforts by British troops did little to stem the problem, the Viceroy ordered the area burned to the ground. Thousands were displaced, and a precious historical neighborhood was gone forever. Not surprisingly, vampire fighting became a valued trade: mercenary vampire fighters roamed the globe, demanding top fees for their services.

While vampires took thousands of victims between 1900 and 1910, their psychological toll on the public may have been even worse. Innocent people were gunned down as panic and paranoia reigned. Some enterprising Americans tried to leaven the stress by opening illegal bars and clubs known as "Curfew-Busters." The locations of these establishments changed often to keep away from the prying eyes of the FVZA.

In general, attempts to skirt the law were the exception and not the rule. Most people in the U.S. honored the curfew, forcing blood-starved vampires to become more brazen, and in the process, more vulnerable. After reaching a peak in 1905, the vampire population stabilized somewhat, before growing again through the Great Depression and the war, until science trotted out its greatest weapon: the vampire vaccine.

1967 LAZLO DISASTER IN SIBERIA

After the development of the vampire vaccine, the United States and the Soviet Union began pouring enormous resources into vampire research. The stakes were great, as it was thought that the keys to immortality lay in vampire DNA. The Soviets based their research at a secret lab outside the small village of Lazo in Siberia. Unbeknownst to the Americans, they made significant progress in the lab and in 1967, under a veil of utmost secrecy, they began animal trials, using chimpanzees as the test subjects.

Sometime in mid-February, disaster struck at the lab when an infected chimpanzee bit a technician. The unfortunate man was vaccinated, but the experimentally-altered virus he was infected with proved to be immune to the vaccine. As a blizzard descended on the village, cutting off communication with the outside world, the technician came to life and ran amok, biting everyone in the lab. The scientific team, transformed into vampires, left the lab and went to the village to hunt. By the time the storm cleared, the entire town of Lazo was infected.

Faced with an uncontrollable vampire plague, Russian President Leonid Brezhnev was forced to take extreme measures. So, on a bright winter day, a transport rolled into Lazo and left a nuclear weapon in the middle of the town square, while the vampires slept. Once the team was safely out of range, they detonated the bomb.

American officials detected the explosion via satellite and launched an inquiry. The Russians claimed accidental detonation, but American intelligence knew that there were no nuclear installations in that part of the country. The mystery ended in the Summer of '68, when one of the soldiers who had planted the bomb defected to West Germany and told the whole story. The 750 people of Lazo were among the last casualties of the war on vampires.

The mishap created a backlash against vampire research in the United States and thoughout the world. On October 14th, 1970, President Nixon signed into law the Muskie-Fineman Act, halting research on vampire blood. It would be 16 years before the ban was overturned, and vampire blood research began anew, with rigorous safety provisions in place to avoid a repeat of the Lazo Disaster.